What actually is AI?

So you've tried a new feature with a sparkle emoji ✨ next to it, and you're wondering how it works, and why sometimes it is incredibly helpful, and sometimes it is totally useless.

Well, lets understand what "AI" actually is.

What does AI mean? What is and is not AI

Firstly, AI is a broad umbrella term, like how "food" contains soup, sandwiches, and so on.

Some things that are under the AI umbrella:

- autocomplete and spellcheck - aka "text prediction"

- recognising text and objects in images - aka "machine vision"

- asking questions to diagnose problems - aka "expert systems"

- making predictions from older data like weather forecasts - aka "machine learning"

So we've always used "AI" stuff in the past.

What changed? Why everyone is getting so excited about this now

Well, there is a new one under the umbrella too:

- predicting new text based on older text - aka "large language models" or LLMs

This is where you take a huge amount of data; say, all the books in a library; then ask the machine to predict not the next word like autocomplete, but the entire next book.

You've probably already seen this idea before with those memes about seeing what your phone autocomplete thinks about you by always choosing the first suggestion and letting it write out a sentence, and it can output something that almost sounds right. That is what LLMs are doing, but with a much bigger data set than your phone keyboard has.

After reading this far, you will likely be thinking one of two ways:

- Wow, it can let people write entire books in seconds!

- ...but those autocomplete sentences are nonsense, why would you want that?

And both are true. The random nonsense is the core of the "hallucination" problem you might have heard about, getting in the way of LLMs being consistently useful.

Hallucination Why is it making stuff up?

Hallucination is when LLMs generate some text that includes "facts" that aren't true. It might confidently tell you that the sky is green, or that gravity was discovered by Isaac Asimov, and so on.

This is annoying, but when the hallucinations are obvious like this you can pick up on them and ignore them as a mistake, and the rest of it might still be useful.

Until it hallucinates something you don't already know. Like whether the symptoms you're describing indicate a serious health condition. Or if that mushroom is safe to eat. Or if that hat suits you 🧢

But, the big AI companies say they're working on fixing hallucination, so surely it will stop doing that soon, right?

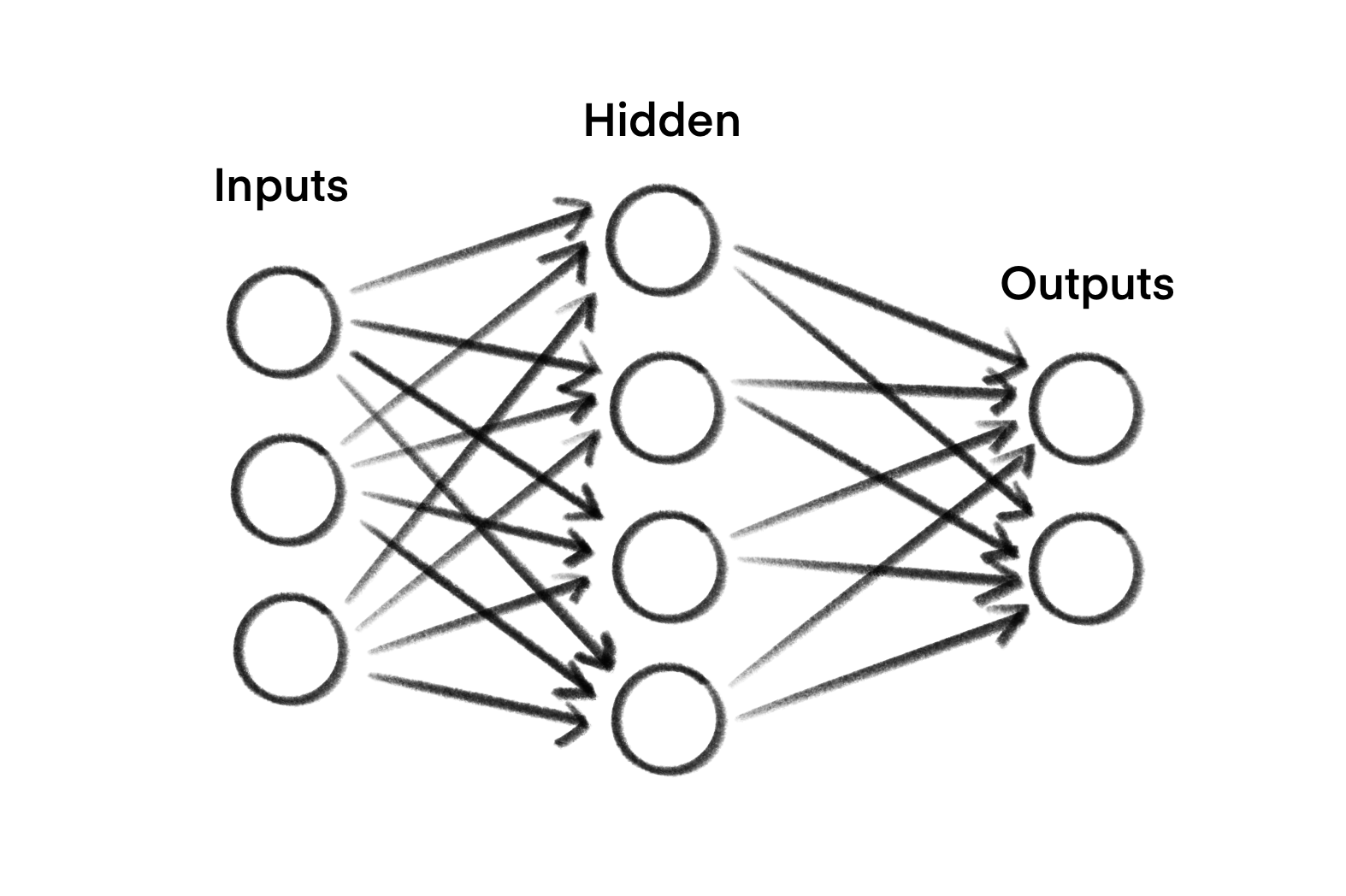

Under the hood Neural networks and how they work

You've probably seen this kind of diagram before in the backround of some AI products; it shows a "neural network" also known as a "model"; it is the engine underneath these AI products which makes it key to understanding why hallucination is such a hard problem to crack. Don't worry, it is almost as simple as it looks. I'll walk you through it.

Layers

In models, the columns you see in the image are called "layers", so I'll describe each layer:

-

Input

The input blobs are information about the question you're using the model to solve. Because it is easiest for computers to work on numbers, this information will be converted to numbers first. How that is done is tedious to explain because it is always different, but it is just important to know we are only working with numbers here.

As a quick example, your context might be "I am driving my" - so each of the words might be converted to a number by assigning a number to every word in the dictionary, so that snippet might become some input values like'42', '805', '1024', '100'. This is called 'tokenization'. And the neat thing is you can tokenize entire chunks, like "Hello my name is" will show up pretty often in English, so it could become a single number instead of four. Or even entire paragraphs. Maybe more. Argh! Now you see why I'm trying to gloss over this, we're already getting into the weeds! -

Hidden

These blobs are math operations, like add, subtract, multiply. Like, that is not an exhaustive list, but we are talking pretty basic math operations here. That is why graphics cards are suddenly in demand; they excel at doing millions of simple operations very quickly.

The ‘hidden' blobs take in the input values, do the operation on them, then pass the result on.

Btw they're only called hidden because they are on the "inside of the box" unlike the inputs and outputs. They're not secret or magic or anything like that. An AI developer can easily go in and poke at them while they're building the model.

-

Output

These blobs are all the possible answers from the model! They take the results and... output them. Thats it. You might have seen a "confidence" before from when a model tries to work out what is in an image, like "cat: 89%, dog: 70%, fish: 2%" — those percentages are the outputs. And thats why it might still list "fish" even though it is so unlikely: the model answers for every possible option, every time. For LLMs generating text, that means they will have a huge number of outputs.

Weights

Ok so that is the blobs, but what do the arrows do? Well, each of the arrows also does a multiplication between zero and one. So if you only wanted to add two numbers together, you would set their weights to one, and all the other arrows you're not interested in would be set to zero, so they get ignored. Or, if you want the average of two inputs, you could set their weights to divide them by half (multiply by 0.5) before you add them.

Parameters

And the combination of the operations done on the hidden layer, and the weights of all the arrows, is the "parameters" you might have heard about. The diagram above is a very simple model, actual models used in LLMs are measured in the billions or trillions of parameters, not (uhhh… *counts in head*) …24, like this diagram above. They might have more hidden layers, or loop some outputs back to some inputs; but they all work basically the same way, even if they're bigger. The huge numbers of parameters are why RAM is also in demand now; you need to load chunks of parameters into the graphics cards very quickly, so quickly that normal hard-drive or SSD storage is too slow.

Cool, so now we understand what a model looks like, but why does that cause hallucinations? And hey, how come the outputs are percentages, not "dog: yes, cat: no, fish: no"?

Training How to make it ‘think’

Working out how to set every one of those trillions of parameters by hand would be very labour intensive and just so, so boring.

So what you actually do when training a model is set them randomly. So roll a bunch of electronic dice, and plug them in.

The side effect of not setting the parameters by hand, is you don't know which ones are doing important work, and which are getting things wrong all the time; so you also can't edit them by hand once they are set, either. You need to work out how good the model is by testing it, changing some parameters, and seeing if you can make it better over time. This is what "training" is.

So to start training, you feed it a lot of data you already know the answers to (e.g. you know this is a picture of a cat, so you expect the "cat" output will be the highest - this is known as ‘labelled training data') and check how well it does. Because you're dealing with random parameters, you don't aim for 100% confidence or correctness, just "better than before" will do.

Off we go, first run, how does it do?

If it does really badly, oh well, shake the dice and roll all the parameters again.

If it does ok, great! You can tweak just a few of the weights or operations at random while leaving the rest alone, and run the test again to see if you get better results. Keep the ones that get better, delete the ones that get worse. It is ‘survival of the fittest'. No literally, the test deciding if a new copy of a model lives or dies is called a "fitness function".

And you just keep running that loop over and over, until you run out of money to pay the electricity bill. Thats it. When it stops getting better at passing the test and you get bored, you package up the winning parameters, and your new model is done.

But sometimes you won't have enough labelled training data to get good results, so you have to train it with unlabelled data (i.e. you don't already know the right answer) and then have a human check it manually instead. This is not ideal because the human will only have a few seconds to check it because the model can produce results waaaaay faster than humans can check them. i am sure this will not become a massive societal problem though

If you are very smart, you may already be detecting a problem with trying to ‘guarantee' this electronic bag of dice will never give bad rolls from unlabelled data checked by stressed and rushed contractors.

The reason adding more data is not fixing hallucinations, is that given a few trillion dice, some of them are always going to roll badly. It does not "know" the right answer, because it is a bag of dice.

So what are they doing about it?

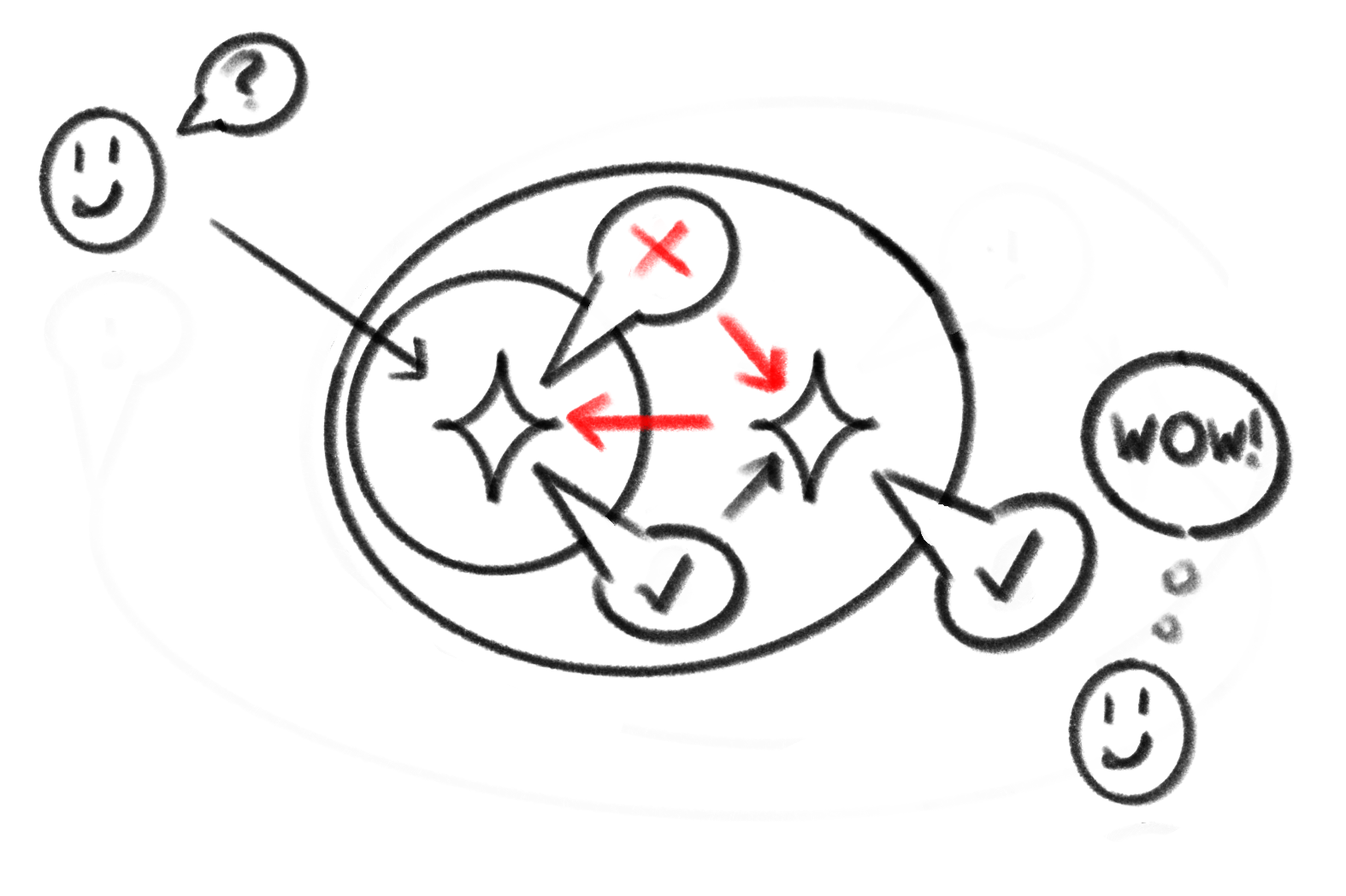

LLMs are like an onion 🧅 Models all the way down

For now the best the companies can come up with to hide the bad rolls in their bag of dice, is to wrap another LLM around it. The inner one tries to answer your question, and the outer one asks itself if that answer sounds right. The outer LLM is still a bag of dice, so it does not ‘know' if an answer is wrong, it is just a guess. It could make checks to databases and take that as input to help (Retrieval Augmented Generation), but the bad roll could have happened before it knows what it is looking up from that database, so those lookups can still fail too. They've also tried 'chain of thought' but... thats just letting it talk to itself by looping some outputs back to the inputs so it doesn't fix bad rolls.

If you use LLM chat bots, you might have seen them delete blocks of their output as you're trying to read it. That is not the chatbot "thinking", that is the outer LLM guessing that the inner LLM just hallucinated (or maybe that it spotted something in the output that the company doesn't like - illegal content, political views, etc).

Wrap enough layers of supervisory LLMs around eachother, and the hope is that you see smaller numbers of hallucinations.

This is like rolling "with advantage" in Dungeons & Dragons. You roll twice and take the better roll. But as any D&D player will tell you, a low chance of failure is not the same as no chance. And with the number of parameters that have to be correct to get the right answer, it has to roll well thousands to millions of times every time you ask a question.

And this, dear reader, is why hallucinations are not being solved. If you're building a company on a pile of dice, you simply cannot guarantee they'll never come up snake-eyes.

So what now? What is it good for?

I've made it sound like a horrific idea to use LLMs, but much like asbestos and radiation, while you have to be careful LLMs are not going to rot you from the inside out, there are some things it is useful for.

My personal guardrails for when it is safe to use LLMs, are:

- You already know it

- It won't affect anyone else

- It is tedious

- You can check it quickly

Guardrails

You already know it

This one should be self-evident if you've read this far. If you don't know about whatever you're using AI for, you can't know if it is hallucinating or not.

Reading a convincing LLM summary does not mean you are talking to an expert who actually knows what they are saying, remember LLMs are a bag of dice underneath.

It won't affect anyone else

If you want to use a LLM to generate some inspiration, or

auto-complete something you would have written anyway, you're not

affecting anyone else.

If you make, or try to influence,

decisions that affect someone else; like using LLM summarisation to

justify denying someone cover, or inventing citations for court cases;

that es no bueno. Consent is key!

It is tedious

Why are you trying to automate away the joy of art and music and

creativity?

That's so very, very sad.

You can check it quickly

I'm a coder, so coding is an example close to my heart. If you use a LLM to generate the next five lines of code, you can quickly read them and check if they're correct. If you generate a whole 10,000 line app from scratch, the chance of you finding all the subtle bugs from the LLM rolling poorly are tiny.

A photographer friend also suggested that culling the 1000 photos from

a photo-shoot to remove duplicates, people blinking etc; down to the

100 you might want to polish up and publish is a good use case for AI.

As is removing bins and stray coffee cups from otherwise great

shots.

You can skim through the 'reject folder' in a

couple of minutes, and you can tell in a second when the

generative-fill has given someone an extra thumb.

Final thoughts you made it to the end, yay!

Be aware of what you're using

I hope by now I've given you a better understanding of how AI ✨ works; and where the dangerous bits are. I hope you can go forth knowing when it is OK to consciously use LLMs to automate tedious work, and when you are in danger of letting a bag of dice tell you how to think and act.

Our greatest strengths as humans are our ability to think and reason for ourselves, create real connections, and share our art and passion with the world. Don't let a robot do that for you!